THE GREY FOLDER PROJECT

A cable to Marseille

BUT WHAT ABOUT FRIEDA?

Hers was the dark understory to my grandparents' "miraculous" escape, the one left behind.

What could it have been like for her after her sister and brother-in-law got their U.S. visas and left, to Berlin and Hamburg for the Russian and Asian visas, and on the arduous but hopeful trip to America? She would have been alone in the Judenhaus, or more likely forced to share a room with a stranger. She would have been alone during the horrifying deportation to Gurs. My father and grandparents and Max would have written letters to her -- and she would have written them back -- but what had happened to those sad anxious letters?

It was with some trepidation that I opened the second folder, Refugee Case File number 10,655.

At first this seemed to be the case with file number 10,655.

The earliest letter, sent by my father in November of 1941(a little more than a year after Frieda had been deported to Gurs), asked if the American Friends could send packages to Frieda "who is in a most desperate state of affairs." Packages of food and warm clothing sent to her had never arrived, my father wrote. And, without these "vital goods," he wrote, "it is hardly imaginable how she could overstand the coming winter."

The answer, although it is not in the file, was certainly that the American Friends Service Committee was not allowed to send goods, only money, to the internees.

I was hoping that there might be a personal exchange with Frieda, or perhaps some evidence of my father's State Department visit to try to save her. But I knew this wasn't very likely.

Ron Coleman, curator of the American Friends' archive, had cautioned me not to set my expectations too high. Most of these files contained only letters about making arrangements to send money to France, he said.

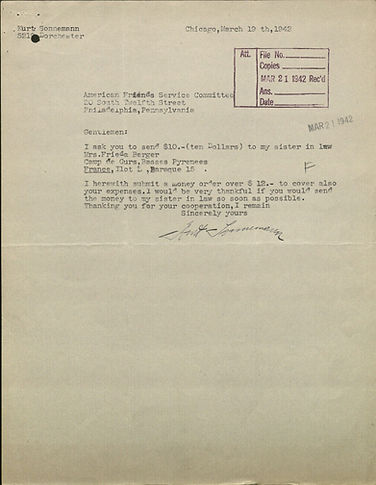

The next letter, dated March 19, 1942, was written by my grandfather, as were the rest of the letters in the file. For the next five months, he sent straightforward requests to send money to Frieda, enclosing money orders in each letter.

The amount of money, always $10, seems so insignificant, but would have been the equivalent of about $146 now. (The $2 alone for AFSC's charge to send the money would be the equivalent of $29.) In the black market of Gurs -- where Frieda could have spent the money for an apple or an egg or possibly even some woolen underwear -- everything was exorbitant.

Following each request, the American Friends Service Committee issued a receipt for the money sent.

BY THIS TIME, FRIEDA had survived in Gurs for nearly two years. The ever-expanding cemetery in the camp gave bitter testimony to the miserable conditions of two harsh winters; that of 1940-41 (when 600 people died within three months) and 1941-42.

For the prisoners, Gurs was "purgatory" if not hell. But gradually some aspects of life there began to improve. Aid organizations, such as the Quakers and Secours Suisse, had rescued young children from the camp, set up classrooms, supplied medications and financed better food supplies for the most vulnerable and fragile prisoners.

The Jewish inmates had also organized to improve the conditions of their incarceration. They elected directors to administer each barrack and section of the camp. A central committee worked with administration to establish a camp-wide mail system, facilities for cooking and laundering, and a dispensary/clinic. The committee procured supplies, from blankets to musical instruments, by establishing a 5 percent tax on all incoming money -- 50 cents of every $10 Frieda received from her family -- to ensure that even those without outside resources could have access to goods to meet their vital needs.The volunteer work of inmates gave purpose to daily life and boosted morale. It is some comfort to think that Frieda, with her sewing skills (and perhaps even with a sewing machine) would have had a purpose to relieve the harsh days at Gurs perhaps repairing worn clothing or teaching other women to sew.

FROM THE GURS HAGGADAH: PASSOVER IN PERDITION, a book about life for the Jewish inmates of Gurs, with a facimile of the Hagaddah, written from memory and published in Gurs in the spring of 1941. Available from Yad Vashem.

The painting is by Fritz Schleifer, who was deported from Gurs in August, 1942, and killed in Auschwitz. It is part of the collection in the Art Museum of Yad Vashem.

WITH ALL I HAD LEARNED about Gurs-- the wallows of slimy mud, the rats and lice, the bitter cold, raging disease and constant hunger--it was astonishing to read how the prisoners worked to counteract these physical degradations with spiritual and creative pursuits. Rabbis, scholars and volunteers organized religious observances holding Sabbath eve services, bar mitzvahs, and weddings in makeshift synagogues. Classes in Bible and Torah study were offered. Thousands attended prayer services and festivities for Passover and the High Holidays. These observances were encouraged by the camp guards to distract inmates from the fear and anger they felt at their situation.

The barbed-wire enclosed Camp de Gurs also became, incredibly, the scene of rich cultural expression. Among the internees were many artists, musicians, writers, poets, performers, singers and photographers. They created programs for the inmates, including plays, poetry readings, art exhibitions, cabaret evenings, operas and chamber music concerts.

THEN CAME THE SUMMER OF 1942 and everything fell apart.

In August of 1942, my grandfather wrote a worried letter. The family had heard the rumors.

"I recently heard, that some of the people from Camp de Gurs in unoccupied France were sent to Poland."

He asked about both Frieda and another woman, the sister of a friend or neighbor in Chicago who had also been interned in Gurs. And he sent $2 for the cost of the cable to find out where they were.

Ten days later, the AFSC wrote back. They had sent the cable to Marseille -- and it cost $3 for the service, so could he please send the additional dollar? -- but such welfare inquiries sent during August were being answered extremely slowly, so it could be weeks before they could notify him.

WHAT NEITHER FRIEDA'S FAMILY or the Quaker organization realized, in this exchange of letters, is that Frieda was already gone. Her fate had been sealed, not only by Hitler's "Final Solution to the Jewish question," but also by the French government's capitulation in 1940 when it signed the armistice agreeing (in Article 19) to "surrender upon demand" any German national to German authorities (in practice, this would apply to all foreign Jews, in both occupied and unoccupied France).

Thus in the summer of 1942, when Theodor Dannecker, the head of the Gestapo's Jewish bureau in Paris, under the direction of Adolf Eichmann, made arrangements for the roundup and deportation of foreign Jews in France, he met no opposition from the French. From June of 1942, victims were deported from Drancy, a detention center set up in a Paris suburb, to the killing centers of occupied Poland.

The horror of the Vel d'Hiv roundup, including more than 4,000 children, in Paris in mid-July was followed by deportations in the unoccupied zone of Vichy France.

THE FIRST DEPORTATION from the unoccupied zone took place in Gurs on August 6, 1942. Frieda was number 11 on the list for the first transport of 1,040.

Those whose names were on the list had to gather in the evening of August 6, dragging their luggage along the road to a holding facility. A roll call took place at 9 p.m.; then buses came to carry loads of 30 people each to the train station at Oloron Sainte Marie; the entire process took until 4 a.m. the next morning. The Quakers gave the prisoners cups of rice porridge to sustain them; other aid organizations gave chocolate, cheese, or fruit -- "the last kindness the prisoners would receive," writes Susan Zuccotti. The train left Oloron mid-morning of August 7, bound for Drancy.

The first transport of Gurs prisoners did not stay long at Drancy. Convoy No. 17, was on its way to Auschwitz on August 10. Of 1,000 people on the convoy, 760 were gassed immediately. Only one man on Convoy 17 was alive at the end of the war.

I RETURNED TO THE FILE from the American Friends Service Committee. Of course, long before I even knew about the file, I had seen the "unknown destination" letter and had known -- though had never become inured to -- the facts of Frieda's murder. Even so, it was heartbreaking to read my grandfather's inquiry about Frieda's welfare -- and the subsequent exchange about sending a cable to Marseille and the cost of the cable--when all the time she had already been murdered in Auschwitz.

I never anticipated that there would be more in the file to horrify me --"news" more than 70 years old that would shock me, right there in the digitized pages of Refugee Case File number 10,655.

Sources:

"The Curse of Gurs: Way Station to Auschwitz" by Werner L. Frank

"The Gurs Haggadah" edited by Bella Gutterman and Naomi Morgenstern

"The Holocaust, the French, and the Jews" by Susan Zuccotti